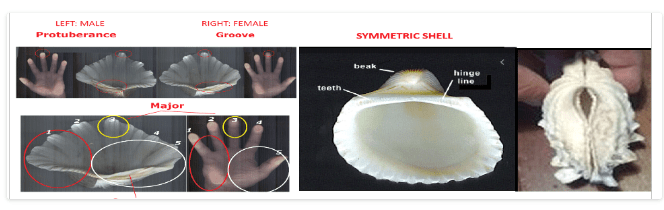

The moment I first became aware of the deep relations between identical forms serving different functions in evolution was in a pawnshop in Montreal. I asked the salesman to show me a shell displayed in the glass counter. To my astonishment, when I held it in my left hand, it fit like a glove — each finger slid naturally into place along its grooves. Out of curiosity, I tried it in my right hand, but the fit was gone.

Figure 1. Shell Fitting Left Hand

I bought the shell on the spot. For the next four or five years, I collected as many shells as I could, determined to study their forms and discover whether they all had distinct right and left sides. Over those years I gathered many specimens and, to my surprise, learned much about form in nature.

That moment in the pawnshop marked the beginning of my long career as an evolutionist, always seeking to understand how things fit together in hidden ways across evolution. As you can see below, what these shells revealed is significant. When they are not symmetrical, as in the example on he left compare to the middle one, the groove of the closing hinge is always on the right shell, while the protuberance is on the left. This division mirrors, in its own way, the asymmetry of the human brain: the left lobe typically more prominent in men, the right more prominent in women .

Figure 2. Asymmetric Shells VS Symmetrical

Although we cannot say with certainty what this left–right asymmetry signifies in humans, my study of hundreds of shells confirmed a consistent pattern in asymmetric forms: the right shell always bears the groove (female), while the left carries the protuberance (male). Other features suggest that these shells also mirror the shape of human hands, as indicated by the circles in the left image. Later, I even encountered shells whose apertures bore a striking resemblance to the female vulva. At this stage, these observations marked the limits of my understanding — yet they already revealed how a single form can serve different functions in evolution.

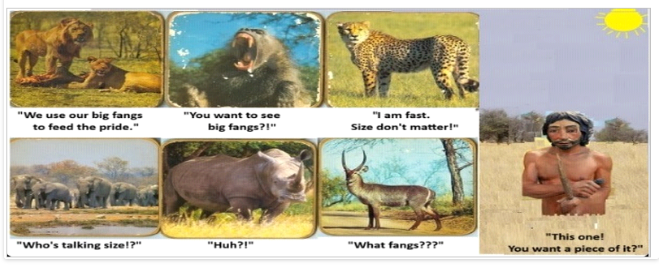

From the late 1960s through the early 1990s, the shells receded into the background of my mind. It was only in the year following my MA that forms returned, just as abruptly as they had in the 1960s. At a garage sale, I came across a set of used beer coasters, which I bought for fifty cents because they reminded me of the role of form in evolution. Soon after, I sketched the cartoon below, illustrating how the same form can serve entirely different functions in the evolutionary process.

Figure 3. Cartoon illustrating how identical forms can adapt differently in evolution.

The cartoon spoke for itself, and with it my shell-related inquiries came to an end in the 1990s as other concerns took precedence. Yet in the early 2000s, as the Internet became more accessible, I stumbled upon new discoveries that drew me back once again to the idea of form in evolution.

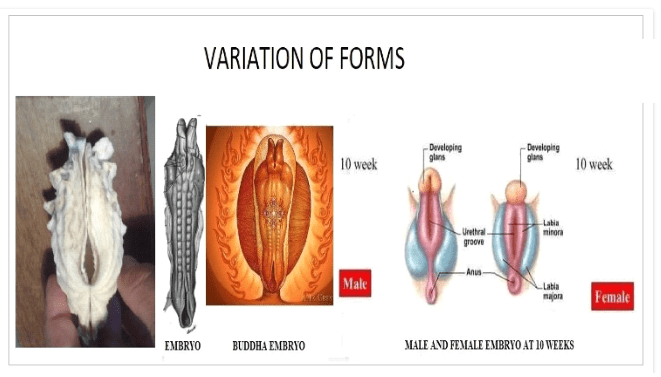

Figure 4. Shell and Embryo

The first realization came when I saw that the shell I once compared to a vulva actually resembled an embryo even more. At the same time, the embryo itself resembles a vulva. For me, this suggested something profound: the principle of life was already present in one of Earth’s earliest organisms we can observe with naked eye, the shell. From that point onward, everything seemed to fit together in principle. It confirmed for me that we are one with the universe — in form — something that can also be encountered through a lifetime of meditation practice, as Yogis describe when they speak of reaching nirvana or enlightenment. My own meditative experiences in the 1970s had already pointed me in this direction, and this discovery helped explain them.

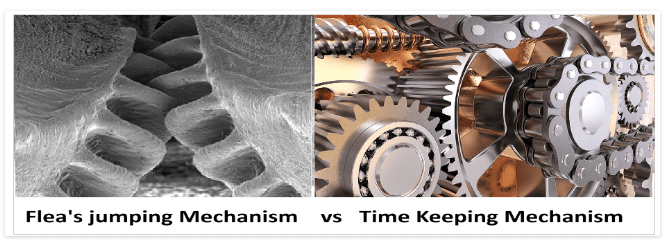

The next revelation struck me with the same force as the pawnshop shell in the 1960s and the beer coasters in the early 1990s: the jumping mechanism of fleas. To my astonishment, it bore a striking resemblance to the gear work of a clock.

Figure 5. Flea Jumping and clock keeping time

What struck me when I first observed the flea’s jumping mechanism, and compared it to the gear system of a clock, was how the same form recurs both in living organisms and in the tools we invent. Life and technology often converge on similar solutions when confronted with the same challenge — how to generate, store, and release force efficiently.

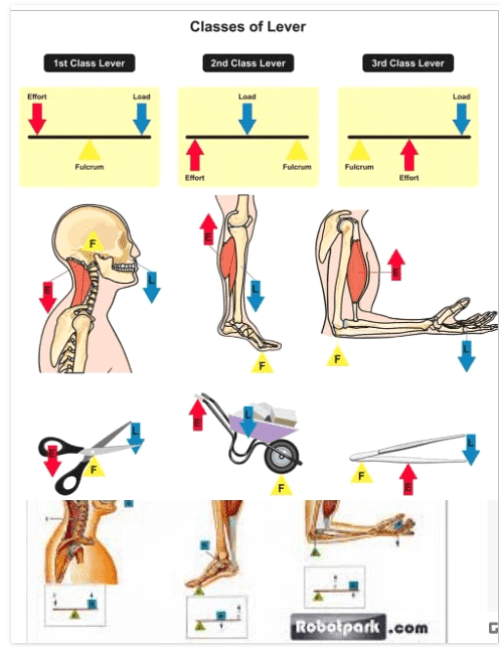

This same principle reappears in the lever systems of the human body, where bones and muscles embody the universal logic of mechanical advantage. Just as gears and springs amplify force in machines, our arms, legs, and jaws function as living levers, applying the same simple yet powerful principle of effort, load, and fulcrum that underlies many human tools, from scissors to wheelbarrows. In both cases — biological and technological — form reveals a deep continuity in the strategies evolution and invention employ to solve problems.

Figure 6. Lever in the Human Body

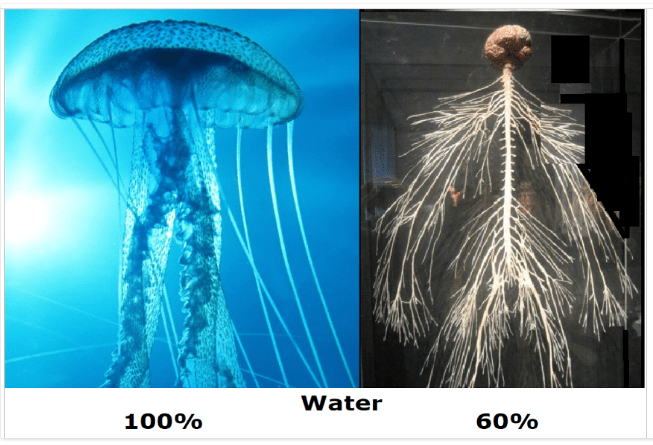

I then discovered that forms, besides serving different functions at different levels, also tend to repeat themselves when placed in the same environment. One striking example came from comparing the human nervous system — a living entity sustained inside a body composed of about 60% water — with a jellyfish, whose entire body lives immersed in 100% water.

Figure 7. Jelly Fish and Nervous System in Water

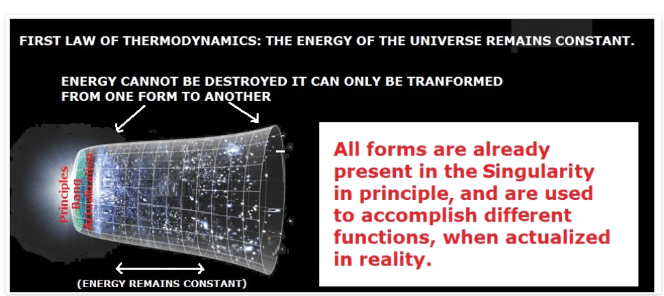

The similarity was again mind-blowing. These forms are undeniably alike, reinforcing my conviction that everything already exists in principle. Just as energy cannot be created or destroyed but only transformed, so too do forms reappear, adapted to different contexts. To illustrate this, I adapted the following image of the Big Bang to my theory. It represents my idea that all forms were already present in the Singularity as potential principles later transformed and expressed throughout evolution.

Figure 8. Energy and Form conservation

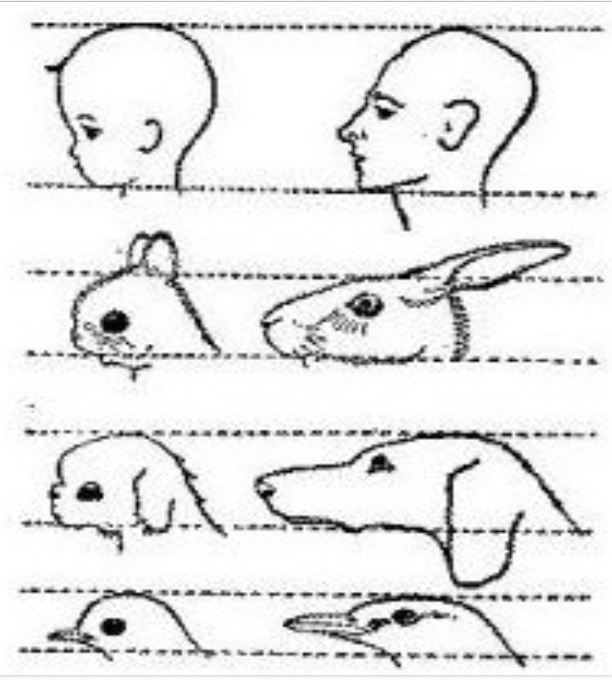

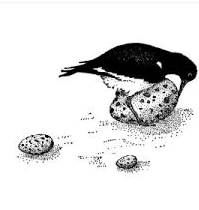

From here, the matter became even more serious. I recalled a schema depicting the process of weaning in animals, a phenomenon noted by Tinbergen, and likewise governed by form. Parents nurture their offspring as long as they display round, infantile features, but begin to wean them once those forms elongate. Form, once again, proves decisive in evolution: it ensures the survival of the young by keeping them protected until they are mature enough to defend themselves.

Figure 9. Form and Weaning

Tinbergen’s research on animal behavior showed that form itself can act as a decisive signal — for example, in the process of weaning, where parents care for their offspring as long as they retain round, infantile features, but begin to withdraw care once those forms elongate. This pattern suggests that form has always been a guiding principle of survival.

Tinbergen also demonstrated that such signals can be exaggerated or distorted, producing what he called supernormal stimuli — stronger-than-natural cues that provoke exaggerated responses. This principle connects the process of weaning to a much broader insight: forms that once signaled nurture and protection can, when amplified, trigger responses out of proportion to their original evolutionary purpose.

This idea opens the door to understanding how anomalies arise in human beings themselves. If, as Tinbergen showed, animals can be misled by exaggerated versions of natural forms, then humans — with our deeply ingrained perceptual responses — may also be vulnerable to similar distortions. What begins as an evolutionary safeguard in infancy (roundness signifying care) can, under certain conditions, be carried into adulthood and misapplied, blurring the boundary between signals of protection and signals of attraction.

This, too, seemed to be present in principle from the very beginning — in the Singularity itself. It deepened my conviction that the Gospel of John had intuited something akin to evolution when it declared: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.’ (John 1:1, King James Version)

In a scientific parallel, I propose: ‘In the beginning was the String, and the String was with the Singularity, and the String was the Singularity.’ (Gaudreault Version, 2025)

From there, I began to examine the role of forms in animal behaviour. Just as in the weaning process — where the changing form of the young signals the time to end parental care — animals can be misled when exaggerated forms are introduced, a phenomenon first described by Tinbergen as supernormal stimuli. This confirmed something I had already realized intuitively long before, since 1981 when I had life-changing experiences with horses: animals do not construct abstract representations of their surroundings as we do. Instead, they react directly to the forms their brains perceive, relying on genomic information that proved viable in the past.

Figure 10. Super Stimuli as Anomalies

In Figure 10, we see striking examples of such supernormal stimuli. A bird prefers to sit on an oversized egg rather than its own, because the exaggerated size triggers a stronger instinctive response. A chick pecks more eagerly at three red dots on a stick than at the single dot on a model of its mother’s beak. A beetle is drawn to the ridges of a beer bottle, mistaking them for an exaggerated version of the ridges on a female’s body. And finally, a duck is compelled to feed carp with their wide-open mouths, while its own chick — visible in the background — is left unattended.

Figure 11. Differential Puberty in Human

I then related these anomalous patterns to human females, who — unlike their male counterparts — tend to retain childlike facial features well into adulthood. I explain this through what I call my “security stick hypothesis.”

During periodic droughts in the Rift Valley of East Africa, forests receded and the Savannah expanded into our former tree habitats. At those times, survival demanded adaptation. In the trees, danger was avoided by climbing quickly to safety. But once we ventured into the open Savannah, there were no branches to grasp. Instead, our ancestors carried sticks — first as a means of security, and later as tools and weapons. These “security sticks” marked a turning point: they allowed humans to objectify reality, to see the environment not simply as an extension of themselves, as it is for other animals, but as something distinct from us. This realization — that the world was separate from the self — was the seed of human self-consciousness. From this foundation came tools, concepts, and eventually theories.

How does this connect to female appearance? In our tree-dwelling past, young were considered “weaned” once they were physically strong enough to pull themselves into trees in times of danger. But in the Savannah, survival depended less on climbing and more on social protection and tool use. Smaller females, already at a disadvantage compared to males, were more likely to survive if they retained juvenile traits longer. By appearing youthful, they elicited prolonged care and protection from the group, increasing their chances of reaching reproductive age.

Over the millions of years of evolutionary time, this process led to the selection of females who carried childlike traits into adulthood — a unique trait among apes. Biologists call this neoteny: the retention of juvenile characteristics into maturity. While humans as a species are considered broadly neotenous compared to other primates, research suggests that this tendency is especially pronounced in females. What might appear at first to be an anomaly is, in fact, an evolutionary adaptation shaped by the long epoch of survival in which females were protected by males.

It is at this point that my explanations become contentious. This phenomenon of neoteny in females is the reason they required protection in nature, before technology, for millions of years — and why males were dominant. Males had the physical strength to live without technology, and so they naturally filled the roles of protectors and providers for millennia, until science transformed human life by allowing the creation of technologies that could be equally used by both sexes. Brute male force was no longer necessary — and even came to be shunned.

Then, in the second half of the 20th century, these roles shifted. While technology was simultaneously destroying one-third of the world’s forests and half of all natural life, the females of our species became the dominant gender. They no longer needed the brute force of their male counterparts, because they had all the tools and technologies necessary to manage on their own. They became the dominant gender.

And, as happens in all species, the dominant side relies on what has succeeded in the past. For women, that meant their childlike appearances — the evolutionary legacy of neoteny. Unconsciously, they began to deploy these traits in the 20th century, first in show business and then more broadly, until such traits became a cultural norm. Their neotenous features gave them an advantage over men, just as male physical strength once gave men an advantage before technology.

Figure 12. Women Using There Forms in Malls

My hypothesis is that the phenomenon of child pornography is directly related to this evolutionary and cultural trajectory. Because women retain childlike traits into adulthood, their appearance unconsciously blurs the boundary between childish forms (which in nature signify care and protection) and adult sexual signalling. This overlap functions as what Nikolas Tinbergen called a supernormal stimulus: an exaggerated or misplaced version of a natural signal that elicits a stronger response than the original.

We already saw this principle in animals in Figure 9, where super stimuli — oversized eggs, exaggerated markings, or artificial shapes — could override natural cues and provoke distorted behaviours. In humans, the same mechanism applies. Childlike features, meant to inspire nurturing, can overlap with sexual traits, producing unconscious confusion in the perceptual and emotional responses of the human brain.

My hypothesis is that if females did not retain these juvenile traits, childish appearances would be associated solely with care and love, and child pornography would not arise as a meaningful phenomenon. What was once evolutionarily advantageous for survival has, in the modern technological and cultural context, produced unintended consequences — with childish traits being unconsciously repurposed as signals of power, attraction, and dominance.

Figure 13. Second Half of the 20th Century Normality’s Degeneration

What we see here is a striking continuity between forms in nature and in culture. In baboons, the rounded swelling of the hindquarters is a clear biological signal of sexual readiness. In humans, fashion such as yoga pants inadvertently exaggerates similar rounded forms. While the intention may be practical or aesthetic, the effect is to create a kind of super stimulus that unconsciously echoes evolutionary signals millions of years old.

This brings us back to the role of neoteny in human females. Childlike roundness and softness were originally traits tied to survival and protection. But in a modern technological society, these same forms are amplified and recontextualized. Unconsciously, they can act as signals of sexual availability — not because of deliberate intent, but because our perceptual systems are still wired to respond to shapes that, in evolutionary time, carried reproductive meaning.

My hypothesis is that the phenomenon of child pornography is tied to this same mechanism. If human females did not retain childish traits into adulthood, there would be no unconscious link between childlike features and sexual signalling. In that case, childish appearance would remain associated purely with care and protection, not with sexuality.

This hypothesis could, in principle, be tested. If there existed groups of people in which women did not retain childlike characteristics into adulthood, one would expect no occurrence of child pornography or related sexual anomalies, since those traits would only trigger responses of protection and gentleness. Even if such groups cannot be found today, the reasoning still holds: if neoteny were absent, there would be no transfer of meaning between childish forms and sexual signals. The universality of neoteny in humans is precisely what explains why this transfer, and its problematic consequences, arise globally.

It is at this point that my contentious case of possession of child pornography comes into play. To understand my situation, one must first understand my intellectual formation. My university trajectory set me apart: I came to see myself as belonging to a different species than Homo sapiens, whose members relate to one another through what might be called their sapienshood or sapiensity.

In my case, earning two general BAs by the age of 37 and an unspecialized MA at 47 left me with no specialization I could share with other sapiens. Instead, I found myself looking at human knowledge from the perspective of the Biosphere. Already in my late twenties, I understood that the Biosphere was in danger if humanity continued on the path of a growth economy. From that point forward, I dedicated myself to its protection — not merely as an individual effort, but by seeking ways for humanity as a species to assume responsibility. And for that, at the age of 33, I decided to undertake a second general BA, to become a generalist, with the intention of formulating in solvable terms the existential crisis, which I had predicted in my mid-therty, and which is with us now, by 2025.

After my formation as a learned generalist, after an unspecialize Master’s in ZooAnthropoSociology, I became as mentally different from other sapiens — each locked into some form of specialization — as humans are physically different from chimpanzees. At times, I even felt more distant. A mere 1.8% genetic difference separates humans from chimpanzees, and yet that fraction accounts for the vast gulf between species. My own difference from sapiens was not genetic but intellectual: a shift in worldview closer to 100%. While they continued to think within the boundaries of human progress and specialization, I was seeing reality from the general perspective of the Biosphere itself.

It was a shift as radical as the one humanity endured when Copernicus, Bruno, Kepler, and Galileo displaced Earth from the centre of the universe. Just as pre-Copernican minds could not easily grasp the heliocentric model, so too my contemporaries — both specialists and laypeople — could not enter the framework I inhabited. I was not speaking from within their sapienshood, but from outside it, in a dimension where the well-being of the Biosphere itself was the central fact, and not progress.

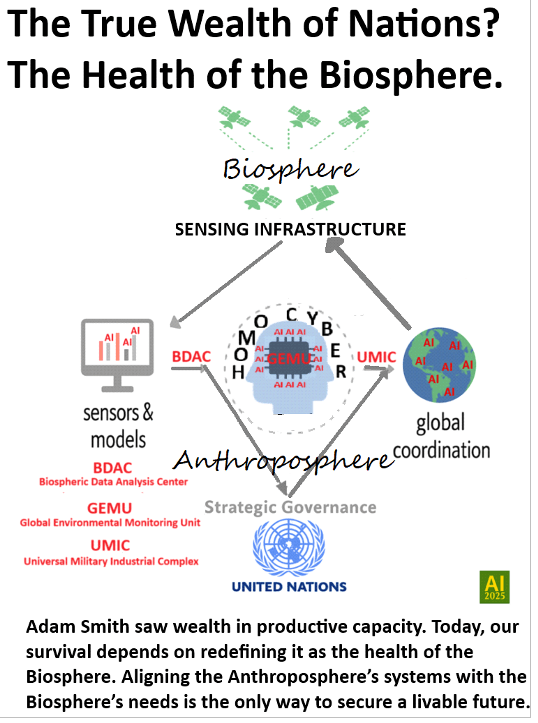

This was the beginning of my self-identification as Homo novus: a human aware, by the end of the 1990s, that our species needed to evolve — though the means by which this transformation would occur was still unclear. Only later, by the 2020s, would I come to see that this novelty could be realized if we learned to use AI so that the Anthroposphere — the sum of our social activities affecting the Biosphere as a whole — could evolve into the Environment’s steward.

Figure 14. With a Little Help from AI

Throughout all this time, I was alone, with no one to communicate my findings to, let alone to share any true intimacy with, since intimacy requires common points of interest. My ideas lay outside the reach of both laypeople and specialists. Yet I did not suffer from this solitude. I never wished to change places with anyone. I remained content within the thread of thought that carried me forward for fifty years, while seeing how humanity misunderstood its relationship with the Biosphere — in much the same way as we once misunderstood our place in the cosmos, before Copernicus, Bruno, Kepler, and Galileo shifted our view from Earth at the centre to Earth as part of a greater whole.

It was in this context of intellectual solitude that another personal reality emerged: for me, intimacy had to be redefined. After more than a decade of social isolation, in the early 2000s, I turned to the Internet as a space for sexual intimacy. I came to identify as a ‘solo-sexual,’ finding connection electronically rather than socially. To me, this was not aberrant but a natural response to my epistemological isolation—the inability to share my ideas or inner experiences with others. I even imagined adding an ‘E’ to the LGBTQ acronym, forming LGBTEQ, to acknowledge that electronic intimacy had become a meaningful part of the human condition

However, by my seventies, things changed. With age, sexual satisfaction became more difficult to achieve. And this is where my research on forms and Tinbergen’s concept of supernormal stimuli returned to me in a deeply personal way. I recognized that what my body responded to when looking at child pornography was not “reality” itself, but exaggerated forms, much like Tinbergen’s birds sitting on oversized artificial eggs rather than their real ones.

Figure. 15 Oversized Egg

From this perspective, I consciously chose to use such stimuli—not because they represented reality, but precisely because they were detached from it. For me, they were electronic tools, a means to achieve necessary biological and emotional release, much like humans have always used mechanical devices for similar purposes. My mind has always remained clear: in eighty years, I have never had an impure thought about real children.

What I responded to was the exaggerated form as a stimulus, not the actual being behind it—just as a bird instinctively sits on an oversized artificial egg, its behavior driven entirely by the superstimulus, having nothing to do with the real, smaller egg that is truly its own. Like that bird, my body responded instinctively, but my mind remained separate and fully aware. Unlike the bird, I knew exactly what I was doing, and I chose to act with one purpose only: to preserve my sanity in the face of decades of profound isolation.

This is why I argue that my case must be understood scientifically. Just as animals can be misled by exaggerated signals, humans too are vulnerable to cultural and technological supernormal stimuli — whether in the form of fashion, advertising, or the Internet. The behavior may seem troubling from the outside, but from the inside, it was, for me anyway, a way to maintain a fragile thread of human intimacy after decades of functional isolation.

If society does not condemn women who, unconsciously, amplify and broadcast sexual signals through cultural forms — for example, by wearing transparent tights in public, which act as exaggerated stimuli — then the same principle should apply to the individual use of comparable supernormal stimuli in private.

Figure 16. Unconscious Cultural Use of Exaggerated Roundish Forms

From an evolutionary perspective, both behaviours stem from the same mechanism identified by Tinbergen: the biological compulsion to respond more strongly to exaggerated forms than to natural ones.

My own life became a living demonstration of this principle. For over fifty years I lived in epistemological isolation, cut off from intimacy with other humans because my intellectual framework lay outside what I have called sapienshood. The thread of thought that carried me forward — focused on the health of the Biosphere and humanity’s evolutionary trajectory — left me without companionship, yet not without need. Sexual climax—the primal release evolution has embedded in us for survival—remained the only form of intimacy available to me, the only way I could feel connection. As the decades passed and I entered my seventies, ordinary stimuli, such as those found on conventional Internet platforms, no longer sufficed. My body, shaped by millions of years of evolutionary conditioning, began to demand ever-stronger stimuli to reach the same release

At that point, I made a conscious decision: to employ exaggerated forms — supernormal stimuli — in order to sustain the physical and emotional equilibrium necessary to continue my intellectual work. This choice was not one of confusion or delusion. Just as Tinbergen’s birds sat on oversized artificial eggs without mistaking them for real eggs, I recognized that these images of children were nothing more than exaggerated triggers of form. My mind always kept form and reality separate. Children were never in my thoughts, nor in my desires. What I let my body respond to was not reality, but form itself — the same principle that governs both evolutionary adaptation and cultural distortion.

Seen in this light, what appears as moral failure is, in fact, scientific evidence: a case study in how forms govern both biology and culture. It shows that even the most reflective human cannot entirely escape the dictates of evolutionary design. My intellectual isolation — which birthed the concepts of Homo novus and later Homo cyber as evolutionary steps toward stewardship of the Biosphere — intersected with my biological reality in a way that revealed, viscerally, the depth of our dependence on form.

This experience reinforced my conviction that we must align the Anthroposphere with the Biosphere through AI, not only to secure planetary survival, but also to confront — with clarity rather than condemnation — the evolutionary forces that continue to shape our most intimate behaviors.

This figure shows the cultural normalization of supernormal stimuli — forms amplified and broadcast unconsciously in public spaces. In fashion, entertainment, and everyday life, women display exaggerated features such as roundness and softness, which act on the same ancient biological wiring identified by Tinbergen. These cues bypass conscious intent, yet they remain powerful: they exaggerate signals that, across evolutionary time, were tied to survival and reproduction.

If society does not condemn the unconscious use of exaggerated sexual signals in public, then neither should I be condemned for consciously recognizing those signals as supernormal stimuli and, in isolation, using them, in my case, to preserve the one evolutionary pleasure essential to my sanity — a pleasure I could no longer attain normally in my 70s, after 20 years of enforced solitary sexuality.

Unlike the unconscious senders of these signals, I recognized their meaning. I understood them for what they were: forms functioning as stimuli, detached from reality. And yet, in my enforced solitude, I still needed to experience pleasure — which is not trivial, but primordial. Sexual pleasure is the evolutionary engine of survival itself, the force that has ensured the continuity of life for millions of years.

My mind’s concern with real children was as distant from me as this bird’s concern with its egg. For that reason, my reliance on supernormal stimuli, child pornography, in private was not an act of impurity, but a conscious adaptation to circumstances — the only way, after decades of isolation, to remain tethered to the evolutionary necessity of pleasure. If society honours and tolerates public displays of exaggerated signals, it should extend the same understanding to their private recognition.

To do otherwise is to punish the scientist for seeing clearly what society itself enacts unconsciously. I rest my case.